Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

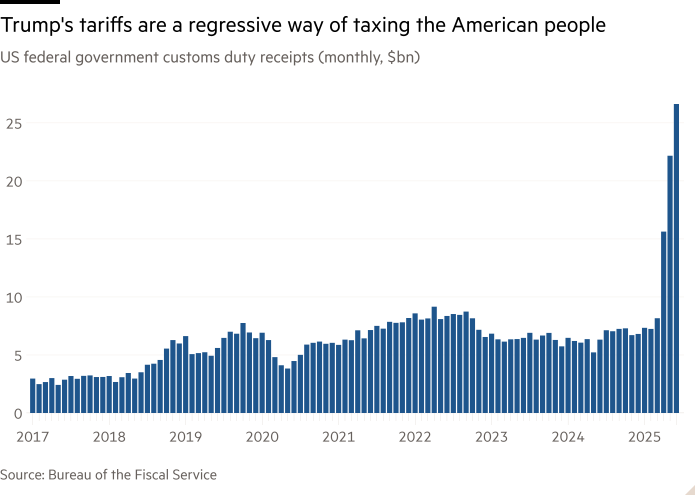

Like a dog to a bone, Donald Trump always returns to tariffs. He is now proposing a modified list of them on a range of countries, including close allies and a number of desperately poor nations, to be imposed on August 1 2025. Will he chicken out, yet again? Who knows? But the chances that he will, or indeed could, get deals able to assuage his irrational mercantilism seem low to non-existent. An irrational man is unpredictable. Maybe this time he means it. If so, May’s already high average US effective tariff level of 8.8 per cent would end up much higher. We would enter a new world.

Glance at just some of what is being proposed: tariffs of 50 per cent on imports from Brazil, 40 per cent on Laos and Myanmar, 36 per cent on Thailand, 35 per cent on Bangladesh, 32 per cent on Indonesia, 30 per cent on South Africa, Sri Lanka and the EU, and 25 per cent on Japan and South Korea. The proposed tariffs are still quite close to those suggested by the extraordinary formula put forward on April 2 2025, in which the determining factor is the ratio of the US bilateral deficit to bilateral imports. (See charts.)

It cannot be said too often that this is nonsensical economics. There is absolutely no reason why bilateral trade should balance. The fact that it does not do so certainly does not show that the surplus country is “cheating”.

Moreover, the overall balance of trade in goods, or indeed in goods and services, is not an aggregate of independently determined bilateral balances. It is the product of the interaction among net factor incomes, capital flows and, above all, aggregate incomes and expenditures. It is, not least, crazy to believe the US can run a huge fiscal deficit without also running large trade and current account deficits, at least as long as the rest of the world is prepared to finance them. What happens if or when the world stops? A financial mess.

In the meantime, the irrational patchwork of tariffs now being proposed would cause large misallocations of resources. One of the points the Trump regime is unable to understand is that tariffs on some goods are a tax on production of others. High tariffs on inputs, such as steel or aluminium, are a tax on producers of the goods that use them. If the latter produce import substitutes, tariffs could at least partially offset such costs. But if they produce exportables, they could not. So, Trump’s tariffs would benefit the least internationally competitive parts of the economy at the expense of the most competitive. Does that make sense? Obviously not.

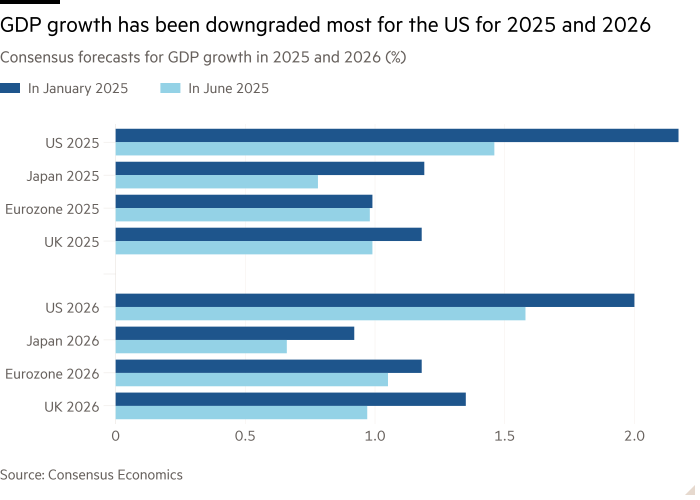

Worse, the entire focus on the goods of the past is ridiculous. What matters is competitiveness in the future. This then is the economic equivalent of attempts to recreate dinosaurs. As MIT’s David Autor and Harvard’s Gordon Hanson note, the challenge for the US today is China’s rise as a technological and scientific superpower. If it is to respond, the US must co-operate with its allies, devote far greater resources to scientific research and welcome talented immigrants — the exact opposite of what Trump is doing. “Make American Great Again”? Hardly. Markets are ignoring these longer-run perils for the US. They might be right. But then they might not.

These tariffs are not just foolish. They are also wicked. Let me take just two examples. The first is Trump’s proposed 50 per cent tariff on Brazil. As he himself has made clear in a letter to President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, this is in response to the trial of Trump’s “mini-me”, Jair Bolsonaro, for seeking to overthrow the results of the last presidential election. Does this sound familiar? As Paul Krugman notes, this is a part of Trump’s “Dictator Protection Program”. Apart from everything else, Trump has no legal authority to use tariffs for this end.

Then there are the brutal tariffs on Laos. According to the IMF, Laos is very poor, with a real GDP per head just 11 per cent of US levels. Its bilateral surplus with the US was also just $0.8bn in 2024! The idea that a superpower should even think of imposing punitive tariffs on such a country is beyond foolish. It is appalling. What makes it irredeemably wicked is that, according to CNN, “from 1964 to 1973, the US dropped more than 2mn tonnes of bombs on Laos . . . More bombs were dropped on Laos during the Vietnam war than on Germany and Japan combined during world war II. It made Laos — per capita — the most heavily bombed country in history.” Have these people no shame?

This administration is headed, declares the White House, by “the best trade negotiator in history”, whose “strategy has focused on addressing systemic imbalances in our tariff rates that have tilted the playing field in favor of our trading partners for decades”. In fact, there was not the slightest chance that deals could have been reached with almost 200 countries, or even 100, in a few months. Moreover, many of the US demands — that the EU should give up the value added tax, for example — are ridiculous. VAT is not a trade distortion: it applies to all goods or services sold into EU markets, as it should, in keeping with the destination principle. Above all, these tariffs would not eliminate US trade deficits anyway.

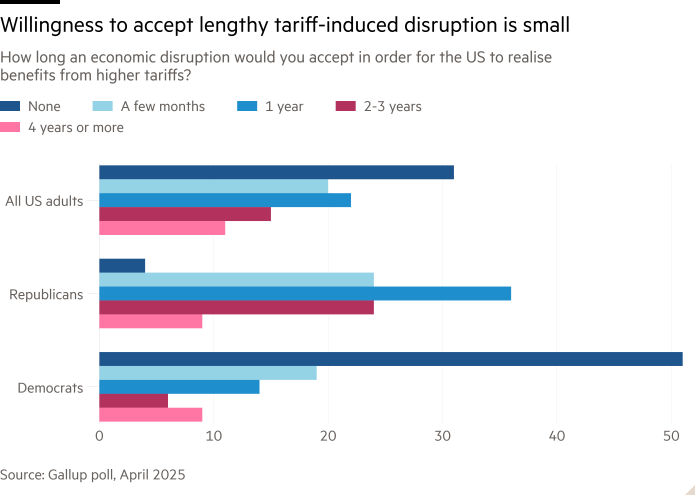

So, what is to be done about this madness? First, we should hope that Trump does indeed chicken out again and again and again, though the uncertainty created would still be costly. Second, there must be retaliation — ideally co-ordinated retaliation — against the US. Third, all members of the World Trade Organization should declare that any trade concessions made to the US will be extended to other members, in accordance with the “most favoured nation” principle. Finally, the other members should also abide by their agreements with one another. The US has gone rogue. The rest of the world need not follow.