As the US retreats from transatlantic security, European countries are scrambling to show that they can take the lead. The focus so far has been on kinetic power: mass industrial military production, artillery supplies and air defence. But that is only part of the challenge.

The Kremlin also excels in non-military means of projecting power. We know the “hybrid” toolkit well by now: the troll farms and conspiracy-spewing state media, the fake news sites, hacks, rent-a-mobs, vote-buying and cyber attacks. If there is a ceasefire in Ukraine, Europe will become an even greater focal point as the information war assets that have been targeted at the US are repurposed.

Can democracies step up in this space? It has been done historically. In the second world war, the British Political Warfare Executive co-ordinated the high-minded BBC and much more subversive, often downright scurrilous radio stations and newspapers where disaffected German soldiers and other exiles undermined the hold Hitler had over occupied Europe.

During the cold war, the US Information Agency supported cultural campaigns that promoted the art of the “free world”, funded anti-Soviet publishing and supported speaking tours and poster campaigns. The jewel in America’s cultural warfare crown was Radio Free Europe, the network of stations that was staffed by exiled dissidents and broadcast back into the communist bloc. At the peak of its reach, 17 per cent of Russians tuned in to Radio Liberty, RFE’s Russian branch.

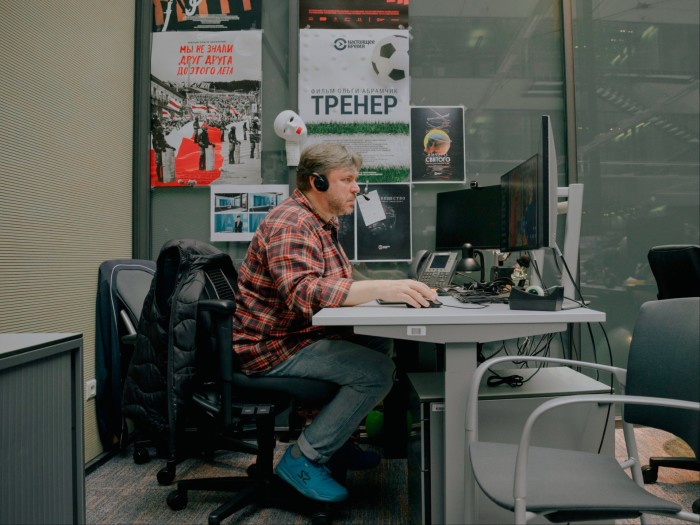

RFE/RL transformed into a multimedia service after the cold war, based in Prague and with 1,700 journalists serving 23 countries: from outright dictatorships like Russia, Belarus and Iran to young democracies such as Ukraine, through to countries where democracy is eroding such as Hungary.

On March 15 the US administration announced it was freezing RFE’s funding. Russian propagandists cheered: “This is an awesome decision by Trump!” pronounced Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of the Kremlin’s foreign propaganda arm, RT, and the Rossiya Segodnya news agency. “We couldn’t shut them down, unfortunately, but America did so itself.”

RFE journalists are accustomed to threats. Four are currently in jail, and many have been deemed “foreign agents” in the regimes they have fled. “I once received an electric shock during torture only for writing for Radio Liberty,” wrote Stanislav Aseev, a Ukrainian author and journalist who was imprisoned for 962 days for his work in the occupied areas of Ukraine. “Now, the ‘enemy of Russia’ is being destroyed by America itself, and my torture seems doubly in vain.”

The Trump administration has also targeted the work of media aimed at Cuba, Asia and the Middle East, as well as Voice of America — a total of $886mn of (congressionally approved) funding to reach a global audience of more than 350mn each week. Foundations and programmes that support democratic initiatives across the world — from anti-corruption NGOs to human rights groups and investigative journalism — have had their (congressionally approved) funding disabled.

Some US agencies are hitting back in the courts, and on March 25 a US district judge issued a restraining order stalling the immediate closure of RFE’s operations. That prompted the government agency in charge to rescind the order to terminate the grant promised by Congress, while reserving the right to remove funding “at a later date”. The grant ends in September anyway. After that it can cease support. And even if RFE manages to salvage its funding for the rest of the year, the overall vector is clear. America is abdicating its post-1945 role as leader of the free world.

As with the hard security issues, there is hope European countries can step in to rescue RFE. A coalition of 12 countries led by the Czech Republic have expressed an interest in supporting it. It’s a moment to show that European countries are serious about filling the vacuum left by America. It’s also an opportunity to think through how European countries, and other democracies no longer able to rely on the US, can compete in the information space, where dictatorships are well ahead of the game. Do European democracies and their friends have to play by the Kremlin’s tactics to compete — or is there another way?

The cold war heritage of RFE takes us right into the complexities of striking a balance between truth-telling and what used to be known as “political warfare”.

RFE emerged in the wake of the second world war, first broadcasting in 1950. The idea was to give anti-communist exiles — politicians and poets, priests and philosophers — the means to express a different vision of their home countries and inspire change within them. Its mission remained strikingly different to stations such as the BBC World Service, Deutsche Welle or Voice of America, which exist to represent their home countries in the world, an act of public diplomacy as well as journalism.

Communist regimes saw in RFE a direct threat, and responded accordingly. In 1981 the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu directed the world’s most famous far-left terrorist, Carlos the Jackal, to blow up the RFE headquarters in Munich. The blast was so vast it knocked out windows a kilometre away and caused more than $2mn of damage. Six people were injured. Over the course of the cold war, other RFE journalists were mysteriously assassinated, while Czechoslovak spies were sent in to poison the salt shakers in the canteen with nightshade. The headquarters in Munich came to resemble a grey fortress, with thick walls and a watchtower.

That’s how I remember them when my father moved to work at RFE after a decade at the BBC World Service in the late 1980s. A political dissident from Soviet Ukraine, in London he had always answered to the editorial direction of British bosses — the head of any language service was always British. At RFE the émigrés were in charge, and he had total freedom to shape his own shows.

This was also the high point of RFE’s audience success. Decades of building up trust meant that when Soviet hardliners arrested Mikhail Gorbachev and shut down all media, 30 per cent of Muscovites tuned in to Radio Liberty. Boris Yeltsin, then president of the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic, went on Radio Liberty and called the state of emergency a coup. He called for crowds to come to the centre of Moscow and vast numbers responded, forming human shields to defend the Russian parliament from the tanks that had pulled into the city. The coup failed. The Soviet Union collapsed.

After the cold war, many in the US questioned whether RFE should be defunded. Wasn’t history over? The services of countries that were joining Nato and the EU were eventually disbanded, but RFE stayed in Russia and other countries to support the transition to democracy. After 9/11, an Iranian service was added. The Afghan service, disbanded in 1993, returned.

More recently, RFE’s mission has gained new relevance. Inside Russia it focuses not just on Moscow’s liberal elites but also on services for the 5mn-strong Tatar population (broadcasting in Tatar), the peoples of the North Caucasus (in Chechen), the Volga region and Siberia. And as Russia has become more repressive, so the demand for the Russian-language services has gone up — YouTube views have jumped from 20mn to more than 70mn per month since 2022. In Ukraine, RFE both broadcasts to the occupied territories and holds the government in Kyiv to account with anti-corruption investigations.

The immediate “European interest” case is not hard to make for much of the work of RFE. In the western Balkans, a region that risks spilling into violence, the services help expose both Russia’s and now also China’s overt and covert campaigns. In the Caucasus, too, the Georgian service is an important media source fighting for fair elections and to fend off domination by a pro-Russian government that will enhance Moscow’s hold over the Black Sea region and critical energy supplies to Europe.

That doesn’t mean that much of RFE wouldn’t change if the Americans were no longer the main supporters. Maybe a deeper focus on certain topics, such as targeted investigations into European sanctions busting, could be in order. Some would dispute the need for an Afghan service, or linear television.

But such editorial slicing and dicing misses the bigger point. If European countries really are going to compete with Russia, rescuing RFE should be seen as part of a wider effort.

When scholars and politicians talk about the effect of international broadcasting they often refer to it as part of “soft power”: it helps create a positive image of the host country. So the World Service “brands” Britain as the sort of place that you can rely on for truth and fairness. RFE does this too to an extent, but it’s perhaps best thought about in the context of another concept — “sharp power”.

“Sharp power” is a term coined by Christopher Walker, vice-president for studies and analysis at the National Endowment for Democracy, a foundation whose congressionally approved funds were also frozen and then partially restored by the US administration. Walker uses the term to describe how autocracies such as Russia have learnt to unite their many streams of non-kinetic influence into a common purpose. “The great advantage the Russians and Chinese have is that they have a large number of assets, from pseudo civil society through to university programmes, state media, corruption and covert campaigns all aiming for a common aim,” he tells me. So when they want to subvert a democratic election, or destabilise a country before a potential invasion, all these assets will work together.

Withstanding this means thinking structurally about how to disrupt the Kremlin’s plans. That could entail teams of investigative journalists and lawyers working across borders well in advance of an election to define, expose and instigate procedures against the corrupt networks that funnel dark money into the country. It would require tech companies to be responsive to digital researchers who spot the sort of covert, co-ordinated mass campaigns that go against their terms of service. It would mean engaging the audiences that are being targeted by Russian campaigns, rather than just preaching to the liberal bubble. The trick isn’t to swamp people with a democratic “fire hose of falsehood” but to create forums where they feel listened to. Where the autocrats use troll farms, we can use online town halls.

Or consider what a sharper approach towards Russia domestically would entail. The stated aim of Europe’s hard security ambitions is to restrain Russian aggression. A more front-footed communication approach would mean a mass-media focus on the Russian military and their families, reporting the dirty truth about corruption among mid-level officers, or the lack of payments for dead soldiers’ next of kin.

Simultaneously, there could be co-ordinated action against Russian military supply chains. Investigators at units like the Open Source Centre are getting better at using data from customs and other sources to map every step in the import supply of elements — chromium, for example — that the Russians need to supply their heavy artillery. We can now use that to disrupt their supply with more scalpel-like tools than just the crude sanctions that were used when the war began. When you know the precise shell companies, names of middlemen and transport routes, you can work with banks to stymie those routes; with western companies to improve their export controls; and with journalists and law enforcement to pressure every node in that chain.

Such focus will slow, disrupt and delay the Russian war machine. Paired with the right kinetic policies, it will help make the Russian leadership more serious about peace. If they understand their military is unstable, they can change their calculations around how aggressive they can afford to be.

Just in these examples, we already see the outline of what a democratic network to counter authoritarian “sharp power” could look like. One doesn’t need to use disinformation. Our tools and methods can be very different — aiming for transparency and rule of law where Russia aims for corruption and confusion. But they do have to be intentional, aiming at the vulnerabilities in the Kremlin networks and engaging the audiences that most matter. And they have to be at scale.

While such tactical tools are important for immediate effects, there is another, deeper level of influence: the underlying narrative of why democracy and freedom are worth fighting for in the first place. This was something RFE excelled at during the cold war. The radio stations broadcast readings of banned books. They played modern jazz and hard-to-find rock ’n’ roll. They combined different facets of freedom — artistic freedom, political freedom, national freedom, economic freedom and the freedom to express yourself — into one powerful and mutually reinforcing story.

But now it is the authoritarians, in Russia especially, who have become adept at pushing an underlying narrative. Their main story is that democracy is a sham, that everywhere is corrupt, that we live in a cynical, chaotic world where you can’t tell truth from lies, and where you need a strongman leader to guide you through the murk. This comes with a sense of personal and group identity that is conspiratorial, and that gains its power from making people feel part of a superior in-group. When I worked with researchers at Georgetown University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill recently, we found that just asking about whether Russian culture was superior to others, or whether Russia is a victim, was enough to make a majority of Russians more supportive of the war, and more resistant to the idea of peace.

In a chaotic world, the race is on to see who can best engage with many people’s sense of anxiety and instability. The alternative to the autocratic crowd and the conspiratorial personality is a community where individuals feel they have agency. Digital technology that enables better democratic debate, culture that explores how we can form less authoritarian group identities and policies that show freedom helps to enhance security — all have a role to play.

So how might a pro-democratic sharp power be organised? We can learn here from the negative experience of the cold war and RFE. At its inception, RFE was sponsored by the CIA, under the cover of private donations to a campaign called Crusade for Freedom. The CIA connection was revealed in 1967 — a scandal in the US but one that did not prevent RFE’s audience numbers from actually increasing in the Soviet bloc, where listeners were more interested in engaging with a media associated with the powerful US government than with some inconsequential “foundation”. After that, the governance model changed. RFE became overtly funded by Congress through a board of academics, media and political grandees to safeguard editorial independence. This seemed acceptable — until the US decided to go Awol.

The lessons are twofold. First, that covert methods can backfire and are usually unnecessary. Second, that you can’t rely on a single investor to save democracy.

Coalitions of willing countries can give a better balance. They can reach beyond Europe to Japan, Australia and other mid-sized democracies that see the value of keeping Ukraine and Europe secure in all senses. But you will need non-state players too. Tech companies, or at least the ones that care about liberal democracy. Universities and research labs to understand social dynamics. The entertainment sector and the arts. Businesses that want to show they are willing to not just comply with sanctions, but actually take a role in making the continent more stable.

The example of how to rescue and rebirth RFE is symbolic of how this process can work. And it’s indicative of Europe’s future relationship with America. The US could do this handover in a pragmatic way, facilitating a transition period for governance and funding. In the future, there are many reasons for it to remain one of many supporters of RFE. The RFE Iranian Service, for example, is followed by 10 per cent of the population and is particularly popular among the youth, with 2.2bn views on Instagram in 2024. RFE also tracks Chinese influence in Eurasia.

Another option is for the US to reverse its isolationist trajectory and resume funding, but with less focus on standing up to Russia. But the fear is that the US may choose a more destructive path. Gutting RFE. Selling off what small assets — studio equipment, cameras — there are. Abandoning journalists, often at great risk to their security. It would be a blow to both American soft and sharp power.

Peter Pomerantsev is the author, most recently, of ‘How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler’. He is a senior fellow at the SNF Agora Institute, Johns Hopkins University

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning